In one episode of No Reservations, Anthony Bourdain travels to Cajun country and attends a boucherie, a massive party where families gather to break down and cook an entire hog over the course of a day. The tradition of the boucherie arose because there was no refrigeration, so fresh meat had to be prepared and eaten quickly.

The food and the live music at this particular boucherie is phenomenal. It seems as though every adult in the community is an expert at cooking at least one speciality dish and playing at least one musical instrument. You can see the kids in the community hovering around the action, their faces lit up as they try to absorb and learn as much as they can.

I believe that when my friend Alec talks about “everyday” learning, this is what he means. Learning is informal, immersive, and seemingly effortless. Alec recently shared two YouTube videos with me to highlight what everyday learning can look like. The first is from a documentary, Boxing Gym. The second is from a talk by Alan Kay where he shows footage of a tennis coach teaching a 55-year-old woman to play tennis in about 30 minutes.

Notice that I said, “can look like.” There is nothing everyday about these examples of everyday learning. The reporter who shot the footage of the tennis coach set up the shoot in order to discredit the coach because he was offended by the notion that almost anyone could learn to play tennis in a single afternoon. The reporter had been trying to learn to play tennis for years. And I haven’t seen the documentary, but I’m going to guess that the gym in Boxing Gym is quite a special place.

Alec has repeatedly argued that everyday learning is effective because we get what we need from it; I have repeatedly disputed that. For me, the footage of the tennis coach teaching the woman to play tennis in 30 minutes was not surprising. I have seen what people can do in the right circumstances. I have constructed some of those circumstances myself. When you know what people can do, then the everyday learning that we see everyday is far from “good enough.”

At most boxing gyms, I’m going to receive little tutelage unless I show promise as a boxer. The elite boxers aren’t going to take me under their wing. There is probably a clear pecking order and I will be bombarded with the message: “You're wasting your time and ours. You’re just not that good.” Some young boxers will persevere through that and still get what they need, maybe winning the respect of the other gym members over time. But I’d probably quit and try something else.

At the gym in Boxing Gym, I’m going to guess that, somehow, a culture of mentoring has taken root; everyone helps everyone, regardless of skill level. In fact, the members of the gym probably derive more pleasure from seeing a single unskilled boxer progress than in producing x number of world champions. And that probably isn’t due to self-selection. You start boxing there. You see the elite boxers, the ones you admire and want to emulate, patiently working with that clueless kid. You try it too, and you experience that pleasure. In another episode of No Reservations, an ex-con working at a community kitchen talks about what it was like to find a place for the first time where you checked your ego at the door because there was no need for it. These are life-changing experiences. When you know that these kinds of places exist, it is hard to argue that most of us get what we need.

The boucherie culture witnessed by Anthony Bourdain exists because there is a critical mass of domain and mentoring expertise in the community. That community will be self-sustaining only if that expertise is at a sufficiently high level. If the food and music produced at the boucherie is only mediocre, or if the kids don’t see themselves stepping into the roles of lead cook and lead musician in a few years, then you are going to hear a lot of teenagers asking: “Is it okay if I hang out with my friends at the mall instead?”

I talk a lot about the need to ratchet up our domain and mentoring expertise even higher, beyond what we need to sustain a learning culture. I want to find out what it takes to export a learning culture. It’s not that I want to see neighborhoods with boxing gyms at every corner or that throw boucheries every weekend. It’s that: before we can develop the domain and mentoring expertise we need to coach others effectively, we have to want it; and for most of us, before we can want it, we need to see it and know that it is possible. I want people to experience a boxing gym or a boucherie and wonder: “Gee, why doesn’t this exist for <insert your favorite domain here>?”

I live near Boston and Cambridge where there is a large and vibrant maker community. This maker community is making a determined effort to infuse its DNA into local schools. But the coaching available to kids growing up in the maker community sucks. Not most of it; all that I’ve seen. There is nothing happening that comes close to what I know that people can do given the right circumstances. How is this possible? If you have misconceptions about what people can do, then you will be limited by those misconceptions. The boucherie, the boxing gym, and the tennis coach can’t counter those misconceptions because not enough people have regular firsthand experience with them. If we do learn about them, we marvel at them instead of emulating them.

So here is the challenge as I see it. In order for learning to be effective, whether everyday learning or in-school learning, you need effective coaches. In fact, you need a large number of highly effective coaches so that everyone has regular contact with good coaching. But in order for people to even aspire to be a highly effective coach, they also need to come into contact with good coaching. It’s quite the chicken or the egg problem.

Sunday, July 6, 2014

Friday, July 4, 2014

Self-Concept, Pick-Up Basketball, and Clash of Clans

There are a few reasons why I’m skeptical of using everyday learning as the model for all learning. One of them is the issue of self-concept.

After college, I attended graduate school at the University of California at Berkeley, and two of my closest college friends settled in the Silicon Valley area. My two friends loved to play basketball, and we spent one summer working out and going to local courts to play pick-up basketball games. Now, the courts we were playing on didn’t look anything like the courts in the movie, White Men Can’t Jump. Guys were most definitely not dunking all over the place. But games were super competitive and the people playing in them could play.

I’m not really sure why I allowed myself to get dragged to these games. My friends were good; I was not. Growing up, I had shot around with my sisters and younger brother, but I had never played in any games, so my ball-handling skills were next to nonexistent. When I stepped onto the court, my mindset was to avoid making visible mistakes. I didn’t want the ball passed to me, and I dreaded having to take an open shot. I focused on defense and rebounding. During the hours of practice we did between games, I did next to nothing to work on my ball-handling skills. In games, I dribbled exclusively with my right hand. With a little practice, I could have learned to dribble with both hands (drastically improving my game), but I never did.

One day, we were invited to play a full-court game. Courts were usually so crowded that most games were half-court, and only the best players were able to play full-court. They had four, but we only had three. So the four guys we were playing against scanned the sidelines and picked this young, chubby kid to be our fourth. It was obvious that no one wanted this kid on their team. He had probably been waiting all day to get into a game, but no one ever picked him.

He was a chucker. As soon as he touched the ball, if he was open and in range of the basket, he was going to shoot. It didn’t matter if I was wide-open beneath the basket for a lay up, there was no way in hell he was going to pass the ball. He was probably thinking that he never gets to play in any games and everyone already thinks he sucks, so he may as well make the most of his opportunity and shoot as often as he can. Besides which, if he did pass the ball to one of us, he figured we’d never pass it back.

The situation looked dire. We were shorter and slower than the four guys we were playing against (at 5' 8", I was playing center in our 1-3 zone), and we were saddled with a chucker and me, a half player. It should have been a romp for the other team. But my two friends and I had something that the other team didn’t: great teamwork. We clamped down on the other team on defense and managed to build a small lead.

I’m not sure what the kid, the chucker, was thinking during all of this. He was hurting us on both offense and defense, but we kept passing him the ball and trying to integrate him into our system. We treated him as though he was a fully functioning member of our team, as though we expected him to play smart and play hard, and we didn’t get down on him when he didn’t. At some point, he must of recognized that something different was going on because he stopped chucking the ball and started working with us. He hustled, looked for the open man, passed the ball, and covered his zone. When we signaled him to cut across the court or switch on defense, he did.

We ended up losing that day, but the game went down to the wire. It was exhilarating and I remember being in the flow. I stopped being self-conscious and started looking to push the ball up court and get open for baskets. Anything to help the team. Among the spectators, I’d like to think that some of them could appreciate what we were doing (that some of them were rooting for us), but the vast majority were simply incredulous that the other team was playing this poorly and thought that we had nothing to do with it. For most players at this level, individual skill is more highly regarded than teamwork.

The transformation in the kid that day was amazing. He went from a classic chucker to a team player in the course of one game. Along the way, he picked up some skills for playing in a zone and communicating on the court that he could build on with the right teammates. He felt this. If we had decided to hop in our cars and drive to another court, he would have gone with us. If we had shown up at this court again the next day, he would have joined us. He had decent skills as a player (better than me), but his lack of status on these courts had caused him to pick up bad habits and become a chucker. Once he became a chucker, even the more generous players on the court didn’t want to play with him. His own perception of himself, drawn from how everyone around him perceived him, became self-fulfilling. But it could all be reversed given the right opportunities, the right mentoring and coaching.

Fast-forward twenty years and this scenario is playing out again. I’m playing Clash of Clans in a clan with fifteen other guys. About half of the clan are in middle school. There is a clear and fairly rigid hierarchy in the game. At the top are the innovators. These are the players who design new bases and attack strategies. Then there are the players who copy the innovators, but can internalize those designs and strategies well enough to adapt them for different circumstances. Then there are the players who can copy the innovators, but can’t counter when a design or strategy is countered; they run the script the same way every time. Finally, there are the players who can’t even manage to run the script for a given design or strategy properly. These last guys “suck.”

A few months ago, Clash of Clans introduced clan wars. Before clan wars, you attacked for loot in order to upgrade your base and your troops. When attacking for loot, you can look for easy bases to attack. It is common to attack fewer than one in twenty bases you look at. And your attacks are private. You can share the replays of your attacks, but that is optional. A lot of players who are poor attackers end up gemming (using real money to buy upgrades instead of using in-game currency).

Once clan wars started, you started attacking bases at your own level for the clan, and those attacks are public. A lot of clan members were embarrassed by how much they “sucked” and would go onto YouTube to search for better base designs and attack strategies. As one of the innovators in the clan, I’m not a fan of copying ideas from YouTube or other sources. At a minimum, I feel like you should understand those base designs and attack strategies well enough to modify them. Over time, I offered tips and suggestions, and encouraged the guys to analyze each others’ attacks. Most ignored me, but a couple took up my advice and became incredibly strong attackers. Once that happened, more joined in. At this point, we have over a dozen very strong attackers, which is rare. Most clans that we go up against have 2-3 strong attackers and bunch of other guys that “suck.”

Yesterday, Supercell updated Clash of Clans with some significant changes to how troops behave, breaking most existing base designs and attack strategies. Across the internet, players are waiting for the innovators to absorb the changes and post new YouTube videos. In my clan, there was a great deal of unease. I suggested that we use the next clan war to focus on experimenting with new strategies, and to forget about winning for a while. This unleashed an immediate torrent of new attack strategies on online chat. Up and down the clan, guys are analyzing the impact of the changes and discussing how to deal with them. The level of analysis is impressive. There’s something else that I’ve noticed. If a new guy joins the clan and he “sucks,” there used to be a chorus to kick him out of the clan. Now, a new guy receives a steady stream of high quality advice from multiple members of the clan. It is gratifying to see the guys I once mentored mentoring others, and doing a better job at it than I did.

The pick-up basketball game and my clan in Clash of Clans are both examples of everyday learning. But they aren’t typical examples of everyday learning. In everyday learning, that chubby kid typically becomes a chucker, internalizes that he is a chucker, and remains a chucker for the rest of his life… with his basketball skills plateauing or atrophying. In Clash of Clans, only the elite players are innovators and everyone else settles for copying the elite players. In the world that I envision, everyone receives the opportunities to overcome and exceed those self-concepts if they choose to do so. As far as I can tell, that requires a large number of strong on-court and in-game mentors and coaches. How do we develop them? That’s what I’m working on.

One final note. Overcoming your self-concept and shifting what you believe you are capable of doing (the standard you establish as “good enough” performance for yourself), is only the first step. If that kid worked hard at becoming a good team player and developed a solid team around him, he wouldn’t necessarily win many games. And without that positive feedback from winning, it’s really tough to keep going and maintain the belief that you can do it. When we started that pick-up game, we started in a zone because it complemented our skills as team players and we didn’t think we could match the other team’s athleticism. We started in a 1-2-1 zone, but we couldn’t stop them from scoring against us. After huddling and analyzing the situation, we thought that a 1-3 zone might work better, and it did. We were able to perform that analysis because we had played and experimented with zones many times, and we had an understanding of their strengths and weaknesses. We also had strong analytical skills. Those things all take time to develop, which is why I think coaching is so important. It doesn’t have to be formal coaching. It could just be random guys making suggestions and observations here and there. But I think that pervasive high-quality coaching is necessary to achieve what I envision.

After college, I attended graduate school at the University of California at Berkeley, and two of my closest college friends settled in the Silicon Valley area. My two friends loved to play basketball, and we spent one summer working out and going to local courts to play pick-up basketball games. Now, the courts we were playing on didn’t look anything like the courts in the movie, White Men Can’t Jump. Guys were most definitely not dunking all over the place. But games were super competitive and the people playing in them could play.

I’m not really sure why I allowed myself to get dragged to these games. My friends were good; I was not. Growing up, I had shot around with my sisters and younger brother, but I had never played in any games, so my ball-handling skills were next to nonexistent. When I stepped onto the court, my mindset was to avoid making visible mistakes. I didn’t want the ball passed to me, and I dreaded having to take an open shot. I focused on defense and rebounding. During the hours of practice we did between games, I did next to nothing to work on my ball-handling skills. In games, I dribbled exclusively with my right hand. With a little practice, I could have learned to dribble with both hands (drastically improving my game), but I never did.

One day, we were invited to play a full-court game. Courts were usually so crowded that most games were half-court, and only the best players were able to play full-court. They had four, but we only had three. So the four guys we were playing against scanned the sidelines and picked this young, chubby kid to be our fourth. It was obvious that no one wanted this kid on their team. He had probably been waiting all day to get into a game, but no one ever picked him.

He was a chucker. As soon as he touched the ball, if he was open and in range of the basket, he was going to shoot. It didn’t matter if I was wide-open beneath the basket for a lay up, there was no way in hell he was going to pass the ball. He was probably thinking that he never gets to play in any games and everyone already thinks he sucks, so he may as well make the most of his opportunity and shoot as often as he can. Besides which, if he did pass the ball to one of us, he figured we’d never pass it back.

The situation looked dire. We were shorter and slower than the four guys we were playing against (at 5' 8", I was playing center in our 1-3 zone), and we were saddled with a chucker and me, a half player. It should have been a romp for the other team. But my two friends and I had something that the other team didn’t: great teamwork. We clamped down on the other team on defense and managed to build a small lead.

I’m not sure what the kid, the chucker, was thinking during all of this. He was hurting us on both offense and defense, but we kept passing him the ball and trying to integrate him into our system. We treated him as though he was a fully functioning member of our team, as though we expected him to play smart and play hard, and we didn’t get down on him when he didn’t. At some point, he must of recognized that something different was going on because he stopped chucking the ball and started working with us. He hustled, looked for the open man, passed the ball, and covered his zone. When we signaled him to cut across the court or switch on defense, he did.

We ended up losing that day, but the game went down to the wire. It was exhilarating and I remember being in the flow. I stopped being self-conscious and started looking to push the ball up court and get open for baskets. Anything to help the team. Among the spectators, I’d like to think that some of them could appreciate what we were doing (that some of them were rooting for us), but the vast majority were simply incredulous that the other team was playing this poorly and thought that we had nothing to do with it. For most players at this level, individual skill is more highly regarded than teamwork.

The transformation in the kid that day was amazing. He went from a classic chucker to a team player in the course of one game. Along the way, he picked up some skills for playing in a zone and communicating on the court that he could build on with the right teammates. He felt this. If we had decided to hop in our cars and drive to another court, he would have gone with us. If we had shown up at this court again the next day, he would have joined us. He had decent skills as a player (better than me), but his lack of status on these courts had caused him to pick up bad habits and become a chucker. Once he became a chucker, even the more generous players on the court didn’t want to play with him. His own perception of himself, drawn from how everyone around him perceived him, became self-fulfilling. But it could all be reversed given the right opportunities, the right mentoring and coaching.

Fast-forward twenty years and this scenario is playing out again. I’m playing Clash of Clans in a clan with fifteen other guys. About half of the clan are in middle school. There is a clear and fairly rigid hierarchy in the game. At the top are the innovators. These are the players who design new bases and attack strategies. Then there are the players who copy the innovators, but can internalize those designs and strategies well enough to adapt them for different circumstances. Then there are the players who can copy the innovators, but can’t counter when a design or strategy is countered; they run the script the same way every time. Finally, there are the players who can’t even manage to run the script for a given design or strategy properly. These last guys “suck.”

A few months ago, Clash of Clans introduced clan wars. Before clan wars, you attacked for loot in order to upgrade your base and your troops. When attacking for loot, you can look for easy bases to attack. It is common to attack fewer than one in twenty bases you look at. And your attacks are private. You can share the replays of your attacks, but that is optional. A lot of players who are poor attackers end up gemming (using real money to buy upgrades instead of using in-game currency).

Once clan wars started, you started attacking bases at your own level for the clan, and those attacks are public. A lot of clan members were embarrassed by how much they “sucked” and would go onto YouTube to search for better base designs and attack strategies. As one of the innovators in the clan, I’m not a fan of copying ideas from YouTube or other sources. At a minimum, I feel like you should understand those base designs and attack strategies well enough to modify them. Over time, I offered tips and suggestions, and encouraged the guys to analyze each others’ attacks. Most ignored me, but a couple took up my advice and became incredibly strong attackers. Once that happened, more joined in. At this point, we have over a dozen very strong attackers, which is rare. Most clans that we go up against have 2-3 strong attackers and bunch of other guys that “suck.”

Yesterday, Supercell updated Clash of Clans with some significant changes to how troops behave, breaking most existing base designs and attack strategies. Across the internet, players are waiting for the innovators to absorb the changes and post new YouTube videos. In my clan, there was a great deal of unease. I suggested that we use the next clan war to focus on experimenting with new strategies, and to forget about winning for a while. This unleashed an immediate torrent of new attack strategies on online chat. Up and down the clan, guys are analyzing the impact of the changes and discussing how to deal with them. The level of analysis is impressive. There’s something else that I’ve noticed. If a new guy joins the clan and he “sucks,” there used to be a chorus to kick him out of the clan. Now, a new guy receives a steady stream of high quality advice from multiple members of the clan. It is gratifying to see the guys I once mentored mentoring others, and doing a better job at it than I did.

The pick-up basketball game and my clan in Clash of Clans are both examples of everyday learning. But they aren’t typical examples of everyday learning. In everyday learning, that chubby kid typically becomes a chucker, internalizes that he is a chucker, and remains a chucker for the rest of his life… with his basketball skills plateauing or atrophying. In Clash of Clans, only the elite players are innovators and everyone else settles for copying the elite players. In the world that I envision, everyone receives the opportunities to overcome and exceed those self-concepts if they choose to do so. As far as I can tell, that requires a large number of strong on-court and in-game mentors and coaches. How do we develop them? That’s what I’m working on.

One final note. Overcoming your self-concept and shifting what you believe you are capable of doing (the standard you establish as “good enough” performance for yourself), is only the first step. If that kid worked hard at becoming a good team player and developed a solid team around him, he wouldn’t necessarily win many games. And without that positive feedback from winning, it’s really tough to keep going and maintain the belief that you can do it. When we started that pick-up game, we started in a zone because it complemented our skills as team players and we didn’t think we could match the other team’s athleticism. We started in a 1-2-1 zone, but we couldn’t stop them from scoring against us. After huddling and analyzing the situation, we thought that a 1-3 zone might work better, and it did. We were able to perform that analysis because we had played and experimented with zones many times, and we had an understanding of their strengths and weaknesses. We also had strong analytical skills. Those things all take time to develop, which is why I think coaching is so important. It doesn’t have to be formal coaching. It could just be random guys making suggestions and observations here and there. But I think that pervasive high-quality coaching is necessary to achieve what I envision.

Thursday, July 3, 2014

Long Division and Everyday Learning

Recently, my friend Alec and I have been exchanging emails on the role and effectiveness of everyday learning. Alec believes that all learning should look like everyday learning. While I don’t necessarily disagree with that, I’m not sure that everyday learning is as effective as Alec makes it out to be. It may be a good place to start, but I feel that we need to do much better than that.

So what is “everyday” learning? I’ve been waiting for Alec to define that for me since he’s the one that brought it up, but let me take a stab at it. For me, everyday learning typically has the following characteristics:

When you take on a home improvement project and start going to Home Depot every day, you quickly learn how the store is laid out. Your need is immediate: it’d be a big waste of time if you had to wander the entire store to find one item. The feedback is fairly nonjudgmental: either you can find what you need quickly and efficiently or not. (Okay, I do feel like everyone in Home Depot can tell I’m a noob when I’m wandering around like a lost sheep, but my need almost always outweighs the small discomfort I experience.) And you have plenty of opportunities to apply what you have learned: you make multiple trips and only learn the layout over time.

In terms of its everydayness, how you learn something shouldn’t matter. If you download a map of the local Home Depot and study it for hours the night before, ask a friend who knows the store like the back of her hand to go with you and show you the ropes on your first few trips, or go in blind… it is still everyday learning. In terms of effectiveness, my gut tells me that everyday learning is most effective when there is lots of immediate feedback and when you can take self-concept out of the picture.

As a teacher and curriculum developer, there are things that I do to make school learning more like everyday learning. In general, students are introduced to long division in 4th-grade and master it in 5th-grade. But what if you delivered a truck full of cookies to eight 2nd-graders on a playground and told them that they could keep the cookies only if they could divide the cookies evenly amongst themselves?

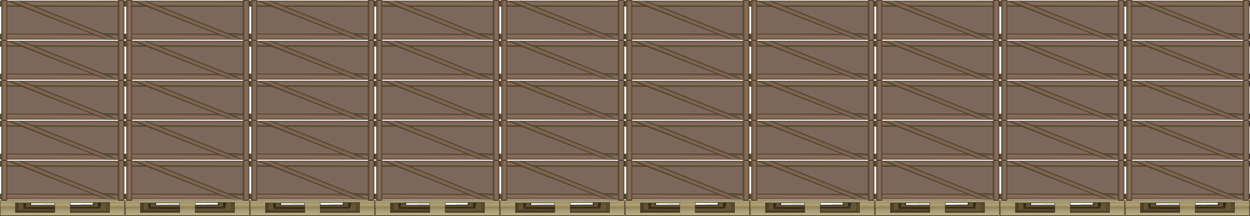

When they open up the truck, the kids find ten pallets:

I’m willing to bet that some enterprising kid would suggest that they start by each taking one pallet. When the two remaining pallets are unpacked, the kids find twenty crates:

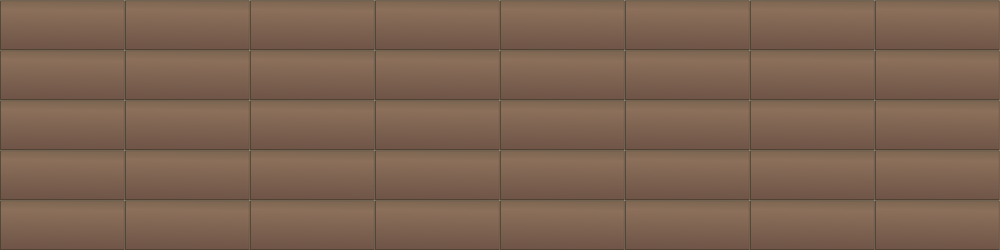

This time, four of the kids suggest that they each take one, and then two, of the crates. When the four remaining crates are unpacked, the kids find forty cartons:

They quickly divide up the forty cartons, each taking five, leaving them with one pallet, two crates, and five cartons each, with nothing left over:

The kids would immediately recognize this as 125,000 cookies if they had ever played Chocolate Chip Cookie Factory: Place Value, but that’s not the point. They just applied the long division algorithm to divide up a million cookies on their own in under half an hour.

Now, if this was really an example of everyday learning, these 2nd-graders would work at some kind of chocolate chip cookie distribution center and they’d be doing these division problems all day. And they’d get very good at them. At first, their solutions would be ad hoc (each problem would be solved as a unique case), but over time, they would start to generalize and find an efficient solution for all problems. How long would that take? Some kids would start doing it right away; others would only do it subconsciously over months.

As a teacher, I can speed things up by designing and sequencing activities to stretch their thinking and by helping them raise things to a conscious level. For example, if a 2nd-grader had to divide three stacks of cookies two ways, he might immediately start by dividing two stacks and opening the third. This would be so obvious to him that he would do it without thinking about it.

But as his teacher, I could ask: “Why don’t you open up all three stacks before dividing them?” This would cause him to pause, think about it, and reply: “Well, that would be silly because you can already tell that each person is going to get one stack. It is faster and easier to start by dividing the big things first.”

I could then follow up by asking him to divide 4 boxes, 6 stacks, and 2 cookies three ways. He might start by dividing three of the boxes and the six stacks before unpacking the leftover box. We could discuss different strategies and explore “what-if” problems together. We could even talk about the benefits of grouping (place value) and how things would be different if everything at the cookie distribution wasn’t in groups of ten. Finally, we could invent a notation system for doing these division problems out on paper. Why would you ever want to do that? Well, imagine that, instead of being on the floor and moving boxes, crates, and pallets around manually, the distribution center became automated and you had to move things around symbolically in a separate control room. How many 2nd-graders would make that transition on their own instead of being laid off and having to find low-wage jobs in the service sector?

These things could happen in everyday learning if you had a good mentor or the distribution center had a surprisingly good training program. But I would say that these opportunities for generalization, reflection, and extension aren’t typical in everyday learning. Remember how I said that some 2nd-graders would start generalizing on their own right away? How did they get that way? Someone modeled it for them, they liked it and internalized it, and started doing it for themselves all the time. My goal as an educator is to guarantee that everyone, whether learning in school or in everyday life, has this same opportunity. I think this only happens if we collectively raise our expectations for what learning looks like so that these models, mentors, and coaches are everywhere for everybody.

When I think about teaching long division using chocolate chip cookies, I’m not thinking about bringing everyday learning into the classroom. I don’t see this curriculum as an example of everyday learning. To me, it is applying basic learning theory. These 2nd-graders have rich and powerful mental models for working with groups. They’ve been working with groups of things in their everyday lives for years. I’m simply leveraging those mental models because it would be incredibly foolish not to. It would take years of arduous work to build parallel mental models for the same concepts in the classroom, and then you’d have two disconnected ways of thinking: one way of thinking for everyday life and a separate way of thinking for the classroom. Who would want that? Crazy.

So what is “everyday” learning? I’ve been waiting for Alec to define that for me since he’s the one that brought it up, but let me take a stab at it. For me, everyday learning typically has the following characteristics:

- It is learning that occurs to meet an immediate need

- The feedback that you receive while learning is nonjudgmental

- You have plenty of opportunities to apply what you have learned

When you take on a home improvement project and start going to Home Depot every day, you quickly learn how the store is laid out. Your need is immediate: it’d be a big waste of time if you had to wander the entire store to find one item. The feedback is fairly nonjudgmental: either you can find what you need quickly and efficiently or not. (Okay, I do feel like everyone in Home Depot can tell I’m a noob when I’m wandering around like a lost sheep, but my need almost always outweighs the small discomfort I experience.) And you have plenty of opportunities to apply what you have learned: you make multiple trips and only learn the layout over time.

In terms of its everydayness, how you learn something shouldn’t matter. If you download a map of the local Home Depot and study it for hours the night before, ask a friend who knows the store like the back of her hand to go with you and show you the ropes on your first few trips, or go in blind… it is still everyday learning. In terms of effectiveness, my gut tells me that everyday learning is most effective when there is lots of immediate feedback and when you can take self-concept out of the picture.

As a teacher and curriculum developer, there are things that I do to make school learning more like everyday learning. In general, students are introduced to long division in 4th-grade and master it in 5th-grade. But what if you delivered a truck full of cookies to eight 2nd-graders on a playground and told them that they could keep the cookies only if they could divide the cookies evenly amongst themselves?

When they open up the truck, the kids find ten pallets:

I’m willing to bet that some enterprising kid would suggest that they start by each taking one pallet. When the two remaining pallets are unpacked, the kids find twenty crates:

This time, four of the kids suggest that they each take one, and then two, of the crates. When the four remaining crates are unpacked, the kids find forty cartons:

They quickly divide up the forty cartons, each taking five, leaving them with one pallet, two crates, and five cartons each, with nothing left over:

The kids would immediately recognize this as 125,000 cookies if they had ever played Chocolate Chip Cookie Factory: Place Value, but that’s not the point. They just applied the long division algorithm to divide up a million cookies on their own in under half an hour.

Now, if this was really an example of everyday learning, these 2nd-graders would work at some kind of chocolate chip cookie distribution center and they’d be doing these division problems all day. And they’d get very good at them. At first, their solutions would be ad hoc (each problem would be solved as a unique case), but over time, they would start to generalize and find an efficient solution for all problems. How long would that take? Some kids would start doing it right away; others would only do it subconsciously over months.

As a teacher, I can speed things up by designing and sequencing activities to stretch their thinking and by helping them raise things to a conscious level. For example, if a 2nd-grader had to divide three stacks of cookies two ways, he might immediately start by dividing two stacks and opening the third. This would be so obvious to him that he would do it without thinking about it.

But as his teacher, I could ask: “Why don’t you open up all three stacks before dividing them?” This would cause him to pause, think about it, and reply: “Well, that would be silly because you can already tell that each person is going to get one stack. It is faster and easier to start by dividing the big things first.”

I could then follow up by asking him to divide 4 boxes, 6 stacks, and 2 cookies three ways. He might start by dividing three of the boxes and the six stacks before unpacking the leftover box. We could discuss different strategies and explore “what-if” problems together. We could even talk about the benefits of grouping (place value) and how things would be different if everything at the cookie distribution wasn’t in groups of ten. Finally, we could invent a notation system for doing these division problems out on paper. Why would you ever want to do that? Well, imagine that, instead of being on the floor and moving boxes, crates, and pallets around manually, the distribution center became automated and you had to move things around symbolically in a separate control room. How many 2nd-graders would make that transition on their own instead of being laid off and having to find low-wage jobs in the service sector?

These things could happen in everyday learning if you had a good mentor or the distribution center had a surprisingly good training program. But I would say that these opportunities for generalization, reflection, and extension aren’t typical in everyday learning. Remember how I said that some 2nd-graders would start generalizing on their own right away? How did they get that way? Someone modeled it for them, they liked it and internalized it, and started doing it for themselves all the time. My goal as an educator is to guarantee that everyone, whether learning in school or in everyday life, has this same opportunity. I think this only happens if we collectively raise our expectations for what learning looks like so that these models, mentors, and coaches are everywhere for everybody.

When I think about teaching long division using chocolate chip cookies, I’m not thinking about bringing everyday learning into the classroom. I don’t see this curriculum as an example of everyday learning. To me, it is applying basic learning theory. These 2nd-graders have rich and powerful mental models for working with groups. They’ve been working with groups of things in their everyday lives for years. I’m simply leveraging those mental models because it would be incredibly foolish not to. It would take years of arduous work to build parallel mental models for the same concepts in the classroom, and then you’d have two disconnected ways of thinking: one way of thinking for everyday life and a separate way of thinking for the classroom. Who would want that? Crazy.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)